Performance Overview

For Q4 2020, the portfolio is up 13.21% and finished the year up 23.47%. The Q4 starting balance was $96,383.61, and finished the quarter at $113,027.88. Contributions to the portfolio during the quarter amount to $3,656.

No stocks were bought or sold during this quarter. During October and November I owned some SPY puts as tail hedges, but I let that position run off in December.

The current allocation of the portfolio is shown in the chart below. Currently, the portfolio consists of discretionary value stocks, oil tankers, deep value, 401k stocks, precious metals, and cash. It can be seen that 66.7% of the portfolio is in stocks, while 33.3% is in cash and safe haven assets. I would prefer to deploy more of the cash to undervalued stocks, but I am remaining cautious despite the market ripping higher towards the end of the year.

During the quarter I received $427.04 total in dividends, which is broken down in the table below.

| Ticker | Quarterly Dividend |

| FF | 8.28 |

| BBSI | 10.50 |

| FRO | 81.50 |

| STNG | 6.80 |

| FE | 48.75 |

| DHT | 43.00 |

| RELL | 24.30 |

| FRD | 7.06 |

| RSKIA | 88.62 |

| EMR | 42.93 |

| COF | 5.50 |

| SPG | 59.80 |

| Total | 427.04 |

My Thoughts

2020 in Review

Going into 2020, my portfolio was a mess. Once upon a time, I was going for a multi-asset strategy. My portfolio consisted of value stocks, emerging markets, commodities, precious metals, money market, and tail hedge puts. In mid-2019 I sold my value stocks to buy a house, which created a gaping hole in my portfolio that remained early in 2020. As the market started to react to COVID, I quickly tried to get my portfolio in order. The primary focus was to reorient my portfolio to mostly focus on value stocks, and taking advantage of the market selloff to buy some quality companies at a discount.

One of the key factors that shaped this year’s performance was holding about $500 in SPY put options. The idea is that they would provide a buffer so that the portfolio could break even even if the market dropped by 20%. In late February these options were doing their job, so I sold them at a value of about $9,000. In hindsight I should have held onto them into March, but I can’t complain. The rest of the portfolio was primarily cash, plus stocks from my current 401k, and some precious metals.

The proceeds of this hedging was used to buy the first batch of quality companies. In March, I bought Capital One, Emerson Electric, and Simon Property Group. To my surprise, the market panic didn’t last long, so the deals quickly dried up.

During April and May I jumped onto the oil tanker trade. While the thesis played out, these companies made a ton of money, the stock returns have been abysmal. I probably bought these stocks at the peak, but that’s the way it goes.

The summer months saw me dip my toe into buying deep value stocks. These are stocks that traded at less than 5 times enterprise value over EBIT. Most of the companies I bought were microcaps, which have a market capitalization of less than $300 million. I didn’t know it at the time, but my timing in buying these stocks was great. The deep value universe got slaughtered during the March selloff, down around 50%. During the summer these stocks turned the corner and rallied all year so that they ended the year down only 7%.

In August I bought some First Energy hoping their bribery scandal is overblown. Finally during the fall I started up the tail hedging strategy again in case of worsening COVID, no stimulus getting passed, and election drama. All of those things happened, but the market ripped higher on vaccine news, causing me a small loss on my SPY puts.

It felt like there was a lot of action in 2020, however I also tried to be measured in my capital allocation. Most of the year I carried a large cash balance, waiting for another chance to buy some undervalued stocks. In hindsight I should have gone all in, but I’d rather act conservatively and survive as an investor.

Luck vs Skill

While I am proud of my performance this year, I am trying to reflect on my decision making. Many of my decisions, and outcomes, were the result of some part skill. However, I am aware I had some lucky tailwinds as well. Since I can be jealous sometimes, I also look at other investors and wonder how much of their results were based on luck or skill.

The way I see it, there is a spectrum of complete luck (roulette wheel) to skill (chess), and most things fall in the middle. Everything in investing probably has some degree of luck involved. But there is a difference between making sound, well thought out decisions, and speculating without even being able to provide a thesis besides “stocks only go up” or “it’s different this time”. It is probably impossible to quantify luck vs skill in investing, but I’m going to ramble on a bit anyways.

I’m not sure if it was luck or skill that I was hedged in February. The outcome of this hedging dramatically impacted this year’s performance.

I chalked it up more towards skill that I was buying in March when everyone was panic selling. On the flip side, if Great Depression 2.0 happened, I’d probably be complaining that I pulled the trigger too early.

Perhaps I got on board with the oil tanker trade too late, my timing being bad luck, or maybe it was a lack of skill.

The deep value universe was turning the corner right when I was buying in the summer. I’ll take this lucky timing since Paul Mueller Co, Barrett Business Solutions, Friedman Industries, and Spark Components have really helped me out.

During the summer, Emerson was up 50%. It was tempting to sell it and get those quick gains. However I am trying to be more disciplined and hold my stocks longer, which worked out because now Emerson is up nearly 100%.

I think you can see there are arguments for luck and skill in many of my decisions. As I look around, I wonder about other investors (or speculators). Is betting on government stimulus, accommodative Federal Reserve, record vaccine development luck or skill? Is it luck or skill to buy cruise ships, airlines, Zoom, NIO and the like? Good for the people who made massive gains this year, but it would probably be wise to reflect on your decision making.

One issue with the stock market is that many people focus on the short term. This short termism makes it easy to think the market is just a casino. Instead, I view owning stocks as owning a slice of a business. Holding a stock for the long term reduces the role of luck since the returns are more driven by business economics. I believe having a long time horizon, and taking advantage of behavioral psychology, allows an investor to make their own luck.

Rationality and Wealth

It seemed like a lot of people lost their minds in 2020. I wish more people would think like Charlie Munger when he says “I never allow myself to have an opinion on anything that I don’t know the other side’s argument better than they do”. Too many people fill their minds with toxic information, surround themselves with toxic people, and allow their cognitive biases to be exploited. An idea that I am developing is that you can’t build wealth (whether that is financial, or in mind/body/spirit) without rational thought. By rational, I mean thought based on first principles, facts, logic, reason, and removing your biases from the equation. You can get rich being irrational, but I think you will have a hard time building long term wealth without being rational.

Discretionary Summary

Discretionary value is the label I’m giving to the positions that are fairly large (~5% of the portfolio) I believe are undervalued and may have the following characteristics: quality business, competitive advantage, misunderstood by the market, or a good company in a heavily sold off industry. The current discretionary value stocks I own consist of Capital One Financial (COF), Emerson Electric (EMR), Simon Property Group (SPG), and FirstEnergy (FE). The table below shows the cost basis, current value, and gains/losses for these positions.

| Avg Price | Cost Basis | Current Value | Current Gain (Loss) | |

| COF | 63.25 | 3,478.75 | 5,436.75 | 56.28% |

| EMR | 41.00 | 3,485.00 | 6,831.45 | 96.02% |

| SPG | 74.50 | 3,427.00 | 3,922.88 | 14.47% |

| FE | 28.00 | 3,500.00 | 3,826.25 | 9.32% |

There has not been a lot of news to report with these stocks. Simon Property Group announced the acquisition of Taubman Centers (TCO), which should close early in 2021. This deal was supposed to happen early in 2020, but it was called off due to COVID19. At least now SPG will pay $43 a share for Taubman instead of the original $52.50.

FirstEnergy drama has deepened this quarter with the firing of their CEO and a couple other executives for misconduct. The company hasn’t disclosed yet what this misconduct was. While FE is looking a little more guilty at the moment than when I made my purchase, the stock has not sold off. I will continue to monitor this company, hopefully the bad news is overblown and the stock will revert back to its pre-scandal levels once the investigation progresses.

Tanker Stocks

Tankers have continued to be disappointing, despite their great profitability this year. Oil tanker spot rates went from a massive peak to a massive trough. Luckily most these companies have used their abnormal profits to shore up their balance sheet. Now that the tankers have to pay less interest on their debt, the break even spot rate is much lower. Recently steel prices have had a large increase, which hopefully means people will be scraping their old tankers soon. One dollar increase in steel prices increases the scrap value of a VLCC by $40k. Plus, less supply of tankers equals higher spot rates to ship the oil.

| Avg Price | Cost Basis | Current Value | Current Gain (Loss) | |

| DHT | 8.17 | 1,755.90 | 1,124.45 | -35.07% |

| FRO | 10.66 | 1,738.29 | 1,013.86 | -41.67% |

| STNG | 26.63 | 1,742.67 | 760.92 | -56.34% |

| TNK | 23.86 | 1,765.88 | 814.74 | -53.86% |

Deep Value

Deep value is a sub-strategy I’m employing in my portfolio. This a quantitative strategy that buys a basket of statistically cheap stocks. The metric I use is EV/EBIT, based on the wonderful book The Acquirers Multiple. Historically, this strategy has provided excellent returns, although it has not kept up with the S&P 500 the past few years. Additionally, I am making an effort to apply this strategy to microcap companies. Microcaps are classified as having a market capitalization between $50M-300M. These small companies are more volatile, but have the potential for attractive returns.

My position sizing is smaller than the discretionary side of my portfolio because I want to own a basket of about 20 stocks. Since this is a quantitative strategy, I do not spend much time analyzing these businesses. The main idea is that these companies are trading at very cheap valuations, and the winners will (hopefully) outnumber the losers.

| Avg Price | Cost Basis | Current Value | Current Gain (Loss) | |

| BBSI | 50.50 | 1,767.50 | 2,387.35 | 35.07% |

| FF | 13.00 | 1,794.00 | 1,752.60 | -2.31% |

| FRD | 5.10 | 1,800.10 | 2,421.58 | 34.52% |

| HXL | 36.80 | 1,803.20 | 2,376.01 | 31.77% |

| MUEL | 26.00 | 1,768.00 | 2,257.60 | 27.69% |

| RELL | 4.45 | 1,802.25 | 1,907.55 | 5.84% |

| RSKIA | 8.25 | 1,740.75 | 2,126.88 | 22.18% |

| SPRS | 1.31 | 1,819.30 | 3,074.70 | 69.00% |

401k and Precious Metals

My 401k is through my current employer and actively receives contributions. The 401k consists of a Blackrock Target Date Fund (which is no longer being funded), and the Oakmark Fund. The Oakmark Fund is a large cap value fund. Since I am actively contributing to my 401k, it will naturally have a growing influence on my portfolio.

I also have a decent allocation to precious metals that are used as a bond substitute, recession and inflation hedge. The table below shows the YTD performance for the precious metals and 401k, which includes the effects of contributions.

| 12/31/19 | 12/31/20 | YTD Gain (Loss) | YTD Contributions | |

| Precious Metals | $7,861.00 | $9,964.00 | 30.52% | |

| 401k | $12,871.20 | $32,252.43 | 14.59% | $14,108.00 |

Tail Hedging

During October and November I implemented the hedging strategy that I had on early in the year. My initial position in October was buying $495 worth of SPY puts. In November, I sold the first batch of puts for $50, and bought another batch for $487. This second batch was sold in December for $175, and I haven’t bought any more since then. The net loss for this hedging was $757, or about 0.67% of the portfolio.

Books I’m Reading

The main book I read this quarter was The Philosophy Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained. Prior to this book, the only other philosophy work I have read was the classic Stoicism work “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius. Whenever I would venture to Wikipedia to read about a philosophy concept, I would get bogged down by all the jargon. This book finally built the foundation for me to understand the high points of philosophy. In fact, I wish I would have read something like this a long time ago because I found the material extremely interesting. Not only does reading about philosophy feed my natural curiosity, but it applies to investing as well (maybe not the weird metaphysical concepts). Understanding why people do the things they do is very important to navigating the investment world. Maybe soon I’ll dig into a specific philosophical work like “On Liberty” by John Stuart Mills…

Cable Cowboy: John Malone and the Rise of the Modern Cable Business is a book I received for Christmas and read within a few days. This book is about John Malone, and his career building TCI and Liberty Media. I was not familiar with Malone, but I knew he was renowned as a great capital allocator so I was looking forward to learning more about him. Malone took over as CEO of TCI in the early 70’s, and transformed the nearly bankrupt company to a cable giant. Once he sold off TCI, Malone has focused on Liberty Media, which he still controls today. Malone’s capital allocation is different from Buffett’s, he utilized debt and focused on cash flows over GAAP earnings. Reading this book makes me want to dig more into cable and media companies in the future.

For more value investing content check out:

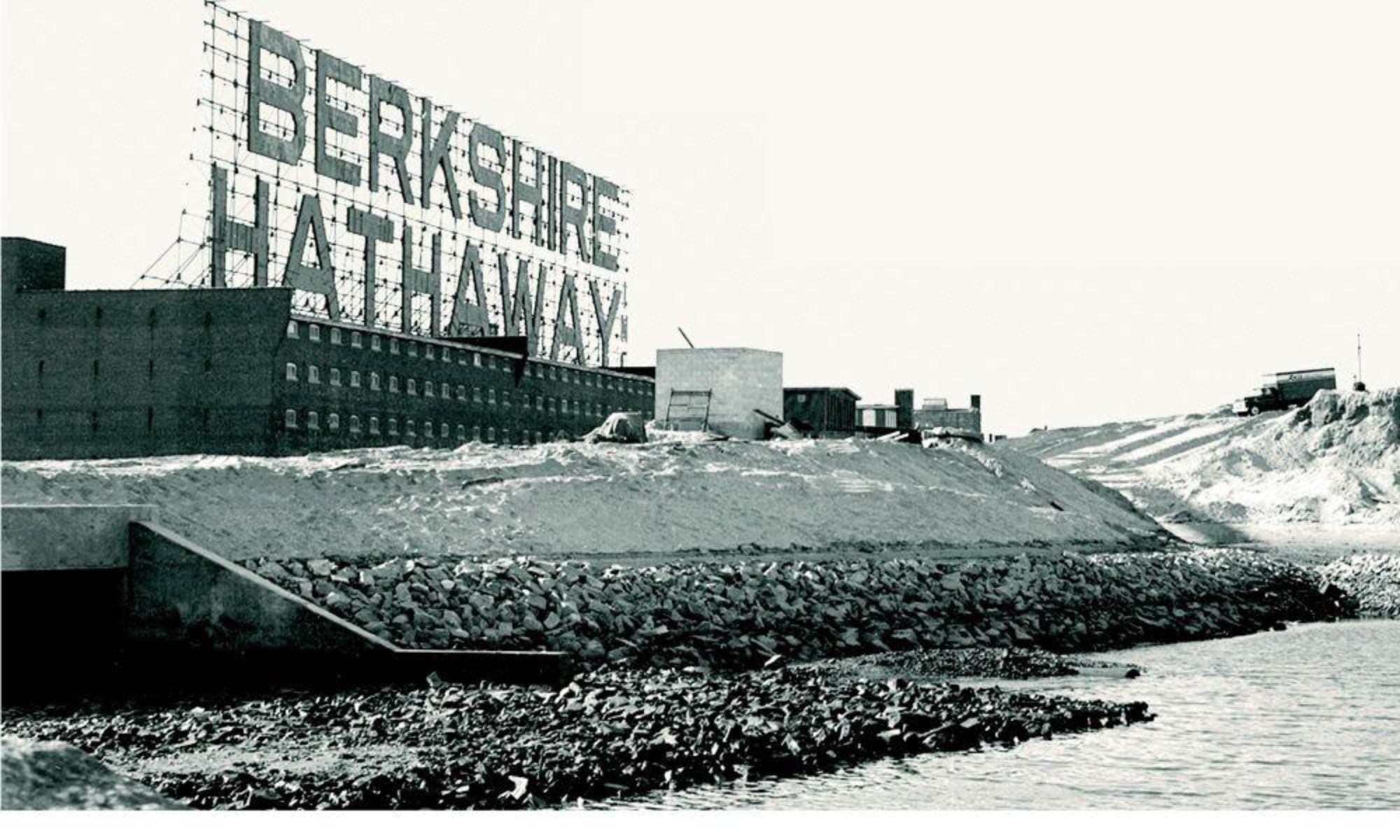

How Berkshire Acquired National Indemnity