This post contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something I may earn a commission. Thanks for your support.

The book “Capital Allocation: The Financials of a New England Textile Mill” is a must read for anyone interested in the history of Berkshire Hathaway. One of the first big moves Buffett did once he took control of Berkshire was to acquire the property-casualty insurer National Indemnity. In this post I wanted to go back and review the details of this acquisition, trying to put things into context. Some of the things I was curious about were “how big of an acquisition was this relative to Berkshire?” and “how did Buffett pay for it?”. But first, we must travel back to the mid 1960’s…

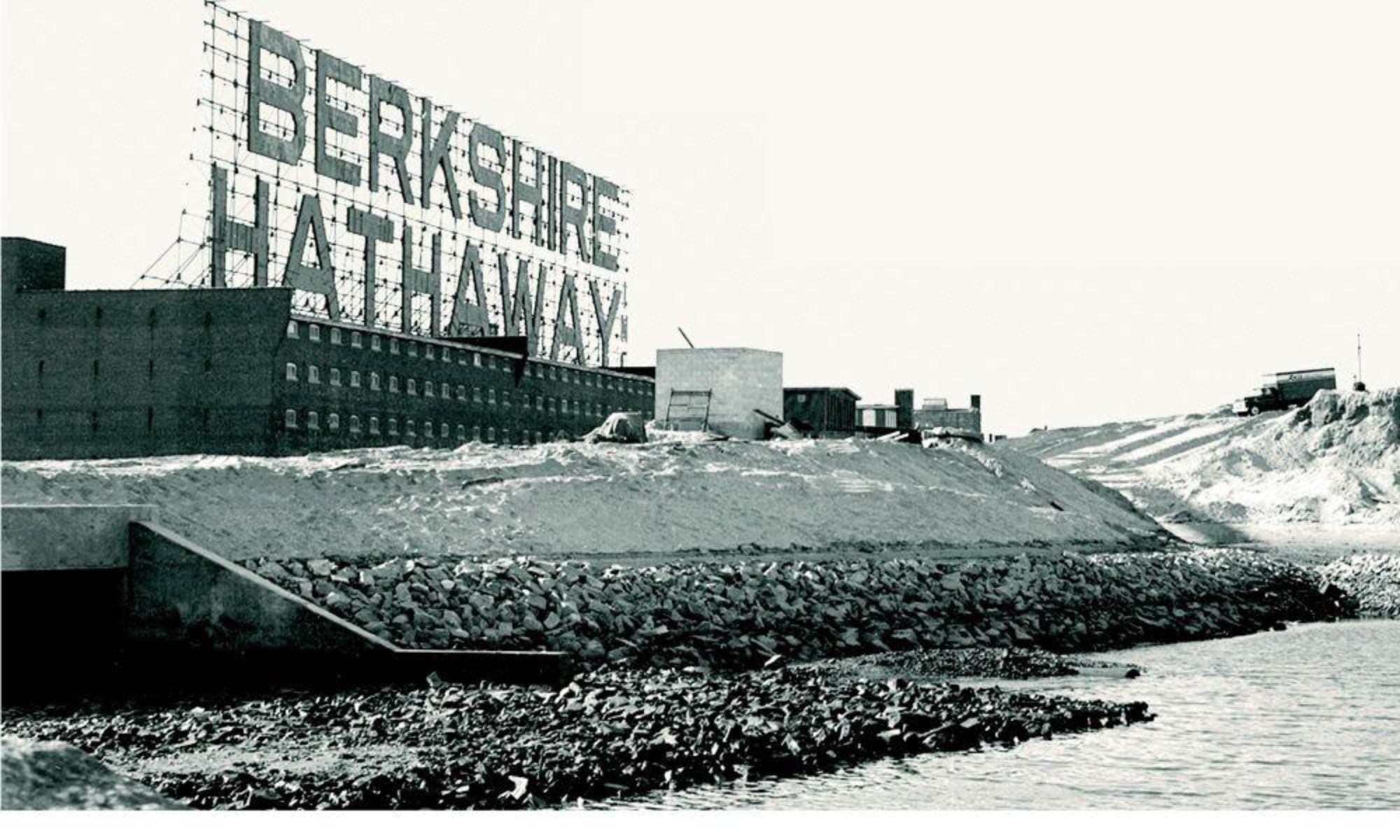

Berkshire in 1967

Before we get into the acquisition of National Indemnity, let’s get a picture of what Berkshire looked like in the mid/late 60’s. When Buffett took control of Berkshire in 1966, it was a struggling, capital intensive textile mill. One of Buffett’s first tasks was to optimize the company’s overhead expenses, capital expenditures, and working capital needs. This freed up cash that could be put to better use, like buying marketable securities.

In 1966, the textile business made about $2.6 million in net income, while the investment portfolio produced about $166k in realized gains. The free cash flow for Berkshire in 1966 was about $5 million. For 1967, the textile business actually lost money, with a loss of about $1.3 million. The newly acquired insurance operations and the investment portfolio bailed out the company by allowing Berkshire to have a total net income of $1.1 million. Revenue for the textile operations fell by 24% from 1962 to 1969. Clearly the industry was challenged, so diversifying Berkshires income stream was a wise move by Buffett.

Assets

Berkshire’s investment portfolio ending in 1966 had a market value of $5.4 million, with approximately the same cost basis. A majority of the portfolio, 87%, was in bonds. The high ratio of bonds was probably due to Buffett holding some capital in reserve for an acquisition. Following the acquisition of National Indemnity, Berkshire’s investment portfolio was booked at a cost of $3.8 million. This portfolio had a market value of $6.8 million, a nifty 77.5% gain in one year. The investments were always recorded on the books at cost instead of market value. Berkshire reported a total of $38 million in assets in 1967. This figure would have increased by 7.9% if the securities were booked to market.

Valuation

During this period, Berkshire often traded below book value, getting down to 57% of book value in 1967. The market cap for Berkshire ranged between $16.8 million, and $20.9 million ($167 adjusted for inflation) in the year that it purchased National Indemnity. Next we will take a look at National Indemnity’s business, and see how a $20 million company acquired the insurer for $8.6 million.

National Indemnity

National Indemnity was a property and casualty insurer founded by Jack Ringwalt in 1940. Another insurance company, National Fire & Marine Insurance Company was an affiliate to National Indemnity. Buffett purchased 99% of these two companies in March of 1967 for $8.6 million. For comparison, this equates to $67 million in 2020 dollars.

NI’s Income

During this time, Berkshire was a capital intensive industrial company, which meant it had very low returns on equity. Buffett realized that a smart strategy would be to redeploy cash from the textile business into a business with a higher ROE that didn’t constantly require upgrading machinery. National Indemnity had a decent ROE that averaged about 11%. The insurer was also growing, having grown premiums at 21% and net income by 15% for the last decade. Average net income for NI was $437,000, while 1966 was an outlier with $1.4 million in profits.

Float

When insurance companies receive premiums, they hold it as a reserve called float. This float can be invested to generate extra income for the company, which is another feature that attracted Buffett to the insurance business. Sometimes insurance companies will write policies that are underpriced, meaning that they end up paying out more for damages than what they received in premiums (they would also hope their investment returns bail them out in the scenario). This would indicate that the float has a negative cost. On the flip side, if the insurer wrote good policies, they would make money on the premiums. This effectively means the float will have no cost. The cost of float generated by National Indemnity was cost free for 6 of the last 10 years prior to the acquisition.

The value of the NI’s float at the time of Berkshire’s purchase was about $17.5 million. The investment portfolio of float was mostly made up of bonds. Additionally the company had a stock portfolio that was about the same size as the shareholders equity. From Buffett’s perspective, he is practically buying a portfolio of stocks and bonds that he could surely optimize for better returns. Just by increasing the investment income on the float by 1% would generate an additional $175k in net income for Berkshire.

While Buffett went on to buy other insurers, namely Geico, National Indemnity is where it all started. To put into context Berkshire’s achievement, in 1967 National Indemnity wrote $12.7 million in premiums. State Farm was the largest property-casualty insurer of the era, with premiums totaling $800 million. Fast forward to 2019, and State Farm is still number one in premiums. However Berkshire is right behind them in second place.

The Purchase

So how did Berkshire acquire a company that was nearly half its size? To fund the purchase, Buffett pulled capital out of the textile business, issued some long term debt, and liquidated some of the investment portfolio. For the textile operations, Buffett optimized the accounts receivables, accounts payable, inventory, and PP&E in order to pull out $4.6 million. Berkshire then issued $2.6 million in 20 year debt at 7.5% interest. Finally, the marketable securities portfolio was reduced by $1.6 million. To me, this is a little interesting that Buffett wasn’t afraid to issue a little debt. He is usually says he is against debt. Additionally, the way Warren pulled out that much capital from the textiles goes to show that he deeply understands the operations of a business.

The book Capital Allocation also discusses a unique way to think of this transaction. When purchasing NI, Buffett was getting a company with a tangible net worth $6.7 million. These securities could then be deployed to marketable securities. Now Buffett was already holding a portfolio of marketable securities of around the same size. So in a sense, Warren is trading his portfolio for National Indemnities portfolio, plus chipping in an extra $1.9 million to get to the full purchase price. Using this mental accounting, National Indemnity operating business was bought for this $1.9 million premium. If we compare the subsequent profit generated by NI to this “purchase price”, we see some absolutely astonishing returns.

Conclusion

Capital Allocation is probably my new favorite business history book since I love nerding out over early Berkshire’s financials. This book shed light on one of the seminal moments in Berkshire’s history. Buffett transitioned the company from a capital intensive textile mill to the giant it is today. The acquisition of National Indemnity set the stage for Berkshire to grow from a $20 million textile business that no one cared about, to the $500 billion behemoth it is now.

For more value investing content check out: